During the early 19th century, Boston was the center of the abolitionist movement. And the area where Boston’s City Hall now stands was a movement hub. Abolition Acre will include commemorative and educational installations that honor and celebrate the many activists who lived and worked in the vicinity and fueled the historic struggle to end slavery.

The Horace Seldon Walking Trail will be anchored by a sculpture expressing the liberating and timeless spirit of abolitionism. And the trail will feature a series of interactive audio-visual kiosks that bring to life the people and events of the abolitionist effort in Boston. Visitors will be able to access these stories through their smartphones, with links to this and other websites for additional information.

Abolition Acre will provide multiple opportunities for educational enrichment. With the aid of key educators, a companion teaching curriculum will be developed for middle and high school students. And ongoing programming will link the abolitionist story with contemporary advocacy for racial justice. For example, a series of educational and arts performances could include a “rap battle” debate between a 19th century abolitionist and a youth organizer campaigning today to end the school-to-prison pipeline.

FOCUS

The exhibit will focus on three of the most important figures in Boston’s abolitionist community of that time: two black and largely unheralded, David Walker and Maria Stewart; and one white and relatively well-known, William Lloyd Garrison.

David Walker (c.1797-1830) was a leader of Boston’s African-American community in the 1820’s, and a co-founder of the Massachusetts General Colored Association that aimed to “promote the welfare of the race by working for the destruction of slavery.” Walker fired the abolitionist movement with his calls for the immediate abolition of slavery, and wrote and distributed a seminal tract, Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World.

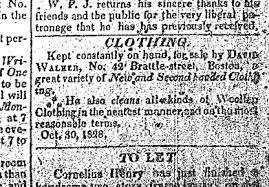

Walker made his living as a second-hand clothing dealer and owned a shop at 42 Brattle Street. A small plaque on Joy Street in Beacon Hill, abutting the site of a house where he once lived, is the only local commemoration of Walker. His gravesite in a South Boston cemetery is unmarked.

Maria Stewart (1803-1879) was the first African-American woman to lecture about women’s rights – focusing particularly on the rights of Black women – and to make public anti-slavery speeches. She was also the first U.S.-born woman of any color to deliver a series of public lectures.

Driven by political and religious zeal, Stewart wrote pamphlets and lectured on a whole range of topics of vital importance to the Black community, including abolition, equal rights, educational opportunities, and racial pride and unity. She was involved with a number of institutions founded by the Black community in Boston, including the Massachusetts General Colored Association and the African American Female Intelligence Society.

William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) was a prominent abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known as the co-founder and editor of the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, which was published every week from 1831 until 1865 when slavery was abolished by Constitutional amendment after the Civil War. (To read copies of The Liberator, click here.)

Garrison formed the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1831 and co-founded the American Anti-Slavery Society. His work was mostly centered at 21 and 25 Cornhill.

TELLING THE WHOLE STORY

Many of Boston’s historic sites, especially those along The Freedom Trail, are must-see stops on any tourist’s itinerary. The Black Heritage Trail is also a popular walking tour featuring the stories and landmarks of Boston’s historic Black community on the North Slope of Beacon Hill. But those sites and activities tell only part of the story. Abolition Acre will compel attention to a whole “hidden history” of courageous and inspiring individuals who were the fulcrum of the abolitionist movement and whose work shaped the future of our city and the nation.

The project will also provide an opportunity to dispel the inaccurate and commonly held notion that most if not all abolitionists were white. In fact, Black people have always been the primary agents in the struggle for their own freedom – as shown by the prominent Black abolitionists who are celebrated in Abolition Acre. In addition to Walker and Stewart, these include Lewis Hayden, Phillis Wheatley, William Morris, Coffin Pitts, James Barbadoes, George Putnam, and William Cooper Nell.

A PUBLIC MESSAGE OF ASPIRATION

The location of Abolition Acre on or close to City Hall Plaza will convey an unmistakable public message. While Boston still has a long way to go on issues of racial justice, it has moved beyond the infamous event that took place on the Plaza in 1976 during the school de-segregation crisis: the assault by a white teenager on Ted Landsmark, a Black lawyer and civil-rights activist, with a flagpole bearing the American flag. The iconic photograph of that incident, seen around the world, tarnished Boston’s image.

Creating the Abolition Acre exhibit near this same spot would be a symbolic statement about Boston’s determination to transcend the ugly and divisive aspects of our past and to work for the just and inclusive society so courageously envisioned by the abolitionists.

As our nation become increasingly racially diverse, it is more important than ever that all of us – and especially younger Americans – learn more about our unheralded racial justice heroes. Abolition Acre offers exciting opportunities to deepen our knowledge of Boston’s history in this regard, and to inspire us to imagine and create a more equitable and inclusive future.